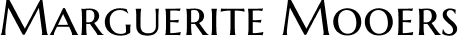

The year is 1945. John Winthrop, marked by leprosy, flees Carville Leprosarium with his thirteen-year-old step-daughter Jenny. Together they navigate the unsettled aftermath of war, secrets, and disease. When Annie Conroy, fleeing abuse and expecting a child, enters their lives, she hopes for refuge. What she finds instead is a web of moral quandaries, hidden disease, and death’s abrupt presence.

Mooers brings The Shelter of Darkness alive not just through plot but through context. Post-war America, rural New York in winter, the stigma of leprosy—all these are more than setting. They are forces acting on her characters. John’s disease isolates him physically and socially. Annie’s fear of her past and her husband’s return shadows every choice she makes. Jenny’s adolescence is caught between loyalty to John and longing for stability.

At the core, the novel is about protection. What does it mean to offer someone shelter when your own soul is exposed? When John harbors Annie and defies the neighborhood’s whispers, he is doing more than hiding disease. He is making moral claims: that caring matters even when society rejects you; that doing what is right is not always safe.

Mooers doesn’t shy from pain. Al Conroy’s abusive presence, Annie’s terror, neighbors’ scorn, the danger that arrives the day Annie gives birth—all of it presses in. Yet within that darkness there are moments of grace: John’s fierce love for Jenny, Annie’s hope, small kindnesses that ripple outward. Light pervades only because it must fight through.

The tension in The Shelter of Darkness isn’t driven by chase scenes or flashy reveals. It’s quieter—by consequences and secrets. When Al disappears, murdered with John’s gun, the question isn’t just whodunit. It becomes: how much can one person carry? When evidence piles up, assuming guilt becomes easier than believing in compassion. Mooers forces both her characters and her readers to see that justice can clash with mercy.

Something haunting me from this novel is how disease becomes metaphor. Leprosy, hidden, contagious, feared—mirrors the secrets people harbor. Annie fleeing abuse; John hiding illness; the community’s fear of difference; the way grief lingers. Mooers uses these to ask: how do we treat those who are marked by what they cannot control? How do we bear shame that isn’t ours?

There is also motherhood in nontraditional form—caregivers who are not mothers, children born into pain, hope in new life even when darkness looms. Annie’s pregnancy is not a beautiful thing only. It is complicated. It’s both a chance and a threat. Jenny’s youth is both vulnerability and strength.

The Shelter of Darkness reminds that history isn’t only in textbooks. It lives in bodies, in landscapes, in people’s prejudices, in the quiet decisions of strangers.